- Joined

- May 11, 2012

- Messages

- 9,801

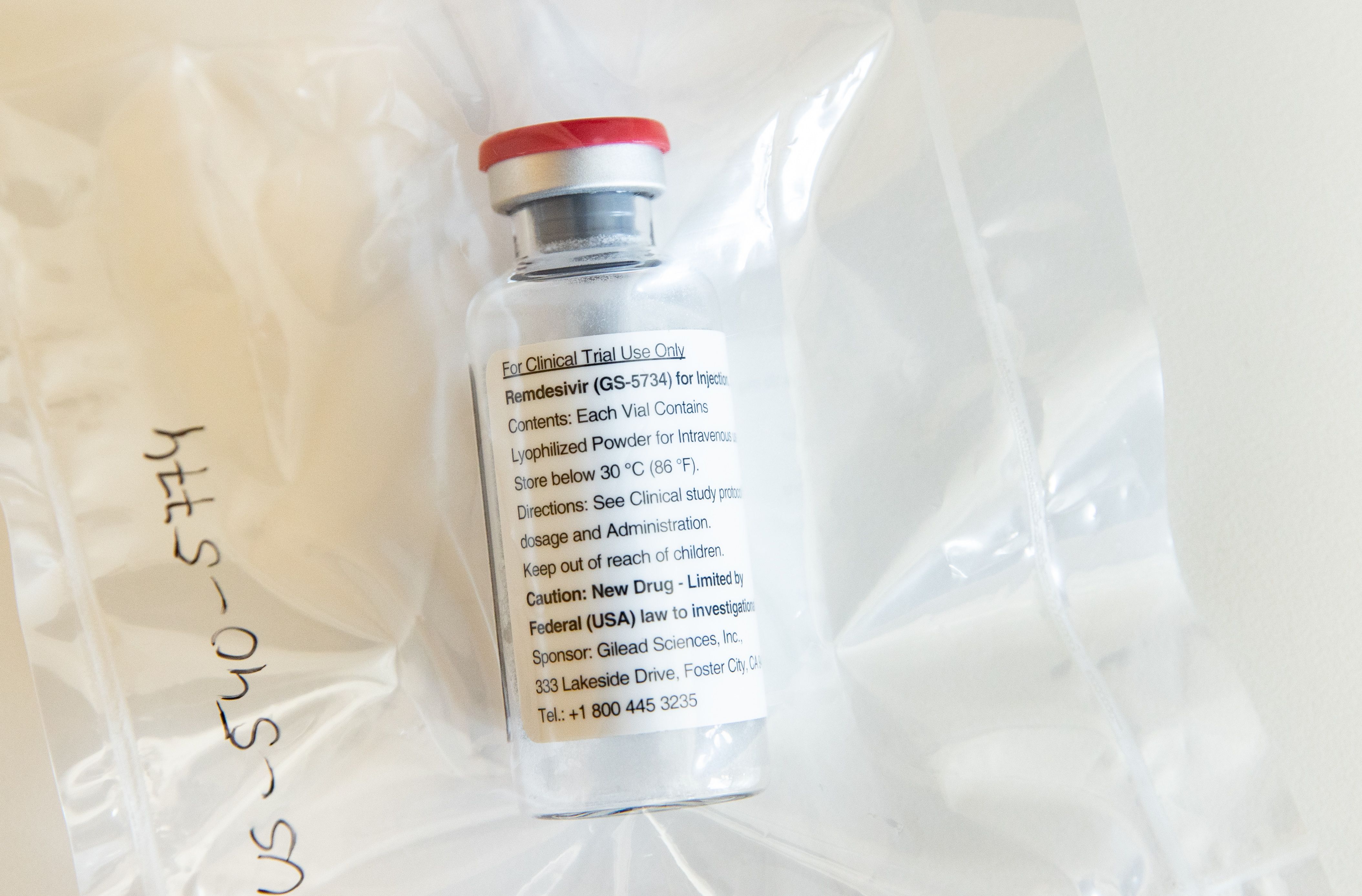

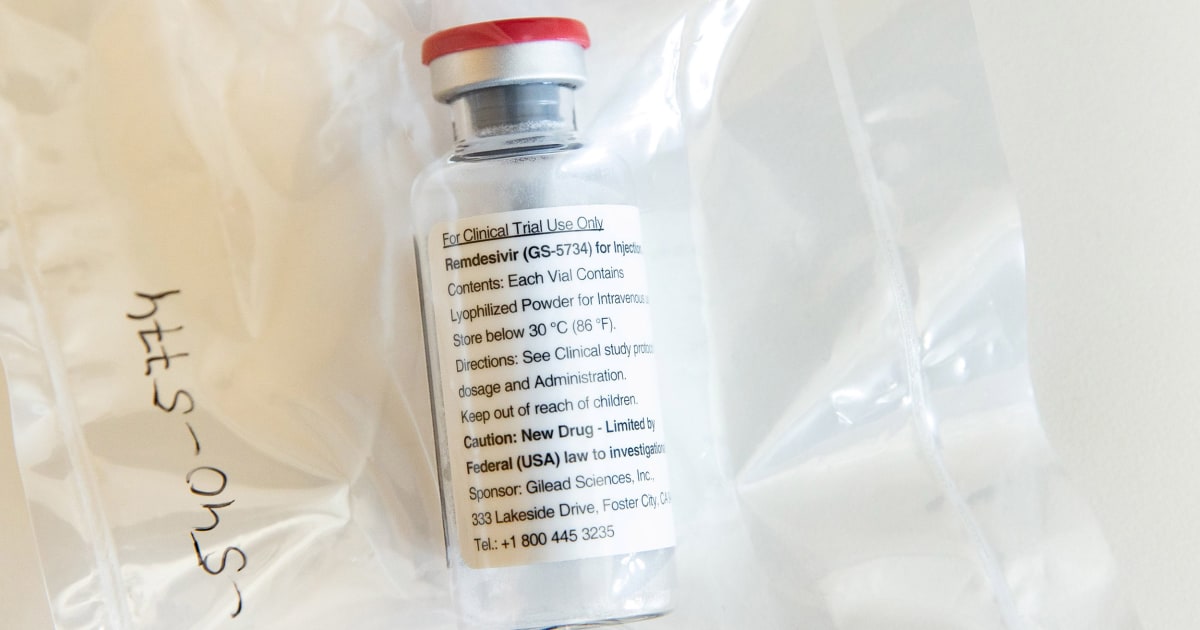

@missy - they haven't written up the trials yet, they are sharing information as they go. I'd guess they are still working out when it works and who it works for. The people that have died here are mostly 70 and over and have often had other underlying health conditions. Another theory that is possible, is that the drugs don't work on older patients or anyone with underlying health conditions (they have been stating the latter in our media) so lets say the majority of critical cases are the people with underlying health conditions in the US, I'd assume that is another reason why it seems like the drugs are not working there.

I think they work, but lets assume that the patient has to have a set range of specific parameters like being treated really early, being under a certain age and having no other health conditions or health conditions not greatly impacted by the virus for the drugs to do what they claim they can do.

The one good thing reading statistics is that for the amount of cases you have much lower death rate % wise than China and Italy did, we know the US has better health resources and places like NY are really gearing up for this far faster than Italy did in response to the crisis.

Being better prepared means you will save more lives. But yes, the sad thing is, if the disease was slowed when it was first entering the US and as many cases as possible were traced and tracked then it wouldn't have been spreading as fast as it is now and that would have potentially saved more people.

The only way to stop it now is a complete shut down and social isolation as demonstrated in countries that did that and really slowed the rate of infection.

@chemgirl - I agree, if the drugs are not working in the US and they are needed for other patients they should not be using them, most of the people overseas using them are not part of the actual trials. I think all they are doing is panicking and attempting to use the medications on severe patients grasping at straws trying to help them, when the sad reality is that it's too late to help them. There is no magic "bullet" or "cure" for severe cases, other than what they are already doing... they have read this stuff works, but the simple truth is they do not understand yet whom it works for.... and that means they do not have a full understanding of when they should and should not be using it.

Australia has a vaccine they have developed (different lab to the Malaria and HIV people) that works and the US has a vaccine that also works but again the reality is that for full testing of that and then full scale production it takes time, they are saying 18 months maybe 12 cutting corners.

People want a solution now. Medically so far there isn't one.... Shutting down the global economy (shutting society down to very basic resources) is a horrible prospect for anyone in politics but it's a matter of doing it for the greater good of everyone.

@missy - we have the same shortages you do, the test kits we were getting were manufactured overseas not here initially so yes we have shortages, we ordered them far far sooner than you did and on our news tonight another researcher has developed a quick pin prick test kits (made overseas) our government has ordered half a million of them;

www.kiis1065.com.au

www.kiis1065.com.au

We have no better resources than you do, we simply have a government that has understood what this disease does and reacted to it far earlier and far better than yours.

I think they work, but lets assume that the patient has to have a set range of specific parameters like being treated really early, being under a certain age and having no other health conditions or health conditions not greatly impacted by the virus for the drugs to do what they claim they can do.

The one good thing reading statistics is that for the amount of cases you have much lower death rate % wise than China and Italy did, we know the US has better health resources and places like NY are really gearing up for this far faster than Italy did in response to the crisis.

Being better prepared means you will save more lives. But yes, the sad thing is, if the disease was slowed when it was first entering the US and as many cases as possible were traced and tracked then it wouldn't have been spreading as fast as it is now and that would have potentially saved more people.

The only way to stop it now is a complete shut down and social isolation as demonstrated in countries that did that and really slowed the rate of infection.

@chemgirl - I agree, if the drugs are not working in the US and they are needed for other patients they should not be using them, most of the people overseas using them are not part of the actual trials. I think all they are doing is panicking and attempting to use the medications on severe patients grasping at straws trying to help them, when the sad reality is that it's too late to help them. There is no magic "bullet" or "cure" for severe cases, other than what they are already doing... they have read this stuff works, but the simple truth is they do not understand yet whom it works for.... and that means they do not have a full understanding of when they should and should not be using it.

Australia has a vaccine they have developed (different lab to the Malaria and HIV people) that works and the US has a vaccine that also works but again the reality is that for full testing of that and then full scale production it takes time, they are saying 18 months maybe 12 cutting corners.

People want a solution now. Medically so far there isn't one.... Shutting down the global economy (shutting society down to very basic resources) is a horrible prospect for anyone in politics but it's a matter of doing it for the greater good of everyone.

@missy - we have the same shortages you do, the test kits we were getting were manufactured overseas not here initially so yes we have shortages, we ordered them far far sooner than you did and on our news tonight another researcher has developed a quick pin prick test kits (made overseas) our government has ordered half a million of them;

New Rapid COVID-19 Tests That Provide Results In 15-Minutes Are Being Rolled Out Next Week

Over 500,000 new rapid COVID-19 testing kits, that are said to provide test results for patients in just 15-minutes, are set to be rolled out across Australia from next week. At the moment, tests can take a number of days to provide answers on whether a person is positive or negative to the...

We have no better resources than you do, we simply have a government that has understood what this disease does and reacted to it far earlier and far better than yours.

Last edited:

300x240.png)