- Joined

- Jun 8, 2008

- Messages

- 56,765

The last time the government sought a ‘warp speed’ vaccine, it was a fiasco

It was 1976, and President Gerald Ford was racing to come up with a vaccine for a new strain of swine flu

President Gerald Ford receives a swine flu inoculation from White House physician William Lukash in 1976. (David Hume Kennerly/Gerald R. Ford Library)

President Gerald Ford receives a swine flu inoculation from White House physician William Lukash in 1976. (David Hume Kennerly/Gerald R. Ford Library)

By

Michael S. Rosenwald

May 1, 2020 at 1:20 p.m. EDT

The federal government has launched “Operation Warp Speed” to deliver a covid-19 vaccine by January, months ahead of standard vaccine timelines.

The last time the government tried that, it was a total fiasco.

Gerald Ford was president. It was 1976. Early that year, a mysterious new strain of swine flu turned up at Fort Dix in New Jersey. One Army private died. Many others became severely ill. The nation’s top infectious disease doctors were shaken.

“They were well aware of the ravages of the 1918 flu, and this virus appeared to be closely related,” political scientist Max J. Skidmore wrote in his book “Presidents, Pandemics, and Politics.” “The officials were concerned about a repetition of the tragedy, or the threat of perhaps an even more virulent pandemic.”

Ford raced to come up with a response, consulting with Jonas Salk and Albert Sabin, the scientists behind the polio vaccine, and in late March he announced an audacious plan for the federal government to produce the vaccine and organize its distribution.

“No one knows exactly how serious this threat could be,” Ford said, with Salk and Sabin by his side, a shocking sight given the two scientists had become enemies over who should get credit for the polio vaccine. “Nevertheless we cannot afford to take a chance with the health of our nation.”

Every American, Ford said, would be vaccinated.

The government had never attempted such an endeavor — both in its breadth and speed.

Almost immediately, there was chaos.

According to Skidmore, a professor at the University of Missouri at Kansas City, insurers were concerned about liability and balked at covering the costs. Manufacturers the government wanted to partner with had similar concerns, prompting Congress to pass a law waiving liability.

One manufacturer produced 2 million doses with the wrong strain. As tests progressed, more scientific problems emerged — even as there were few, if any, signs that a pandemic was materializing. In June, tests showed the vaccine was not effective in children, prompting a public squabble between Salk and Sabin over who should be vaccinated.

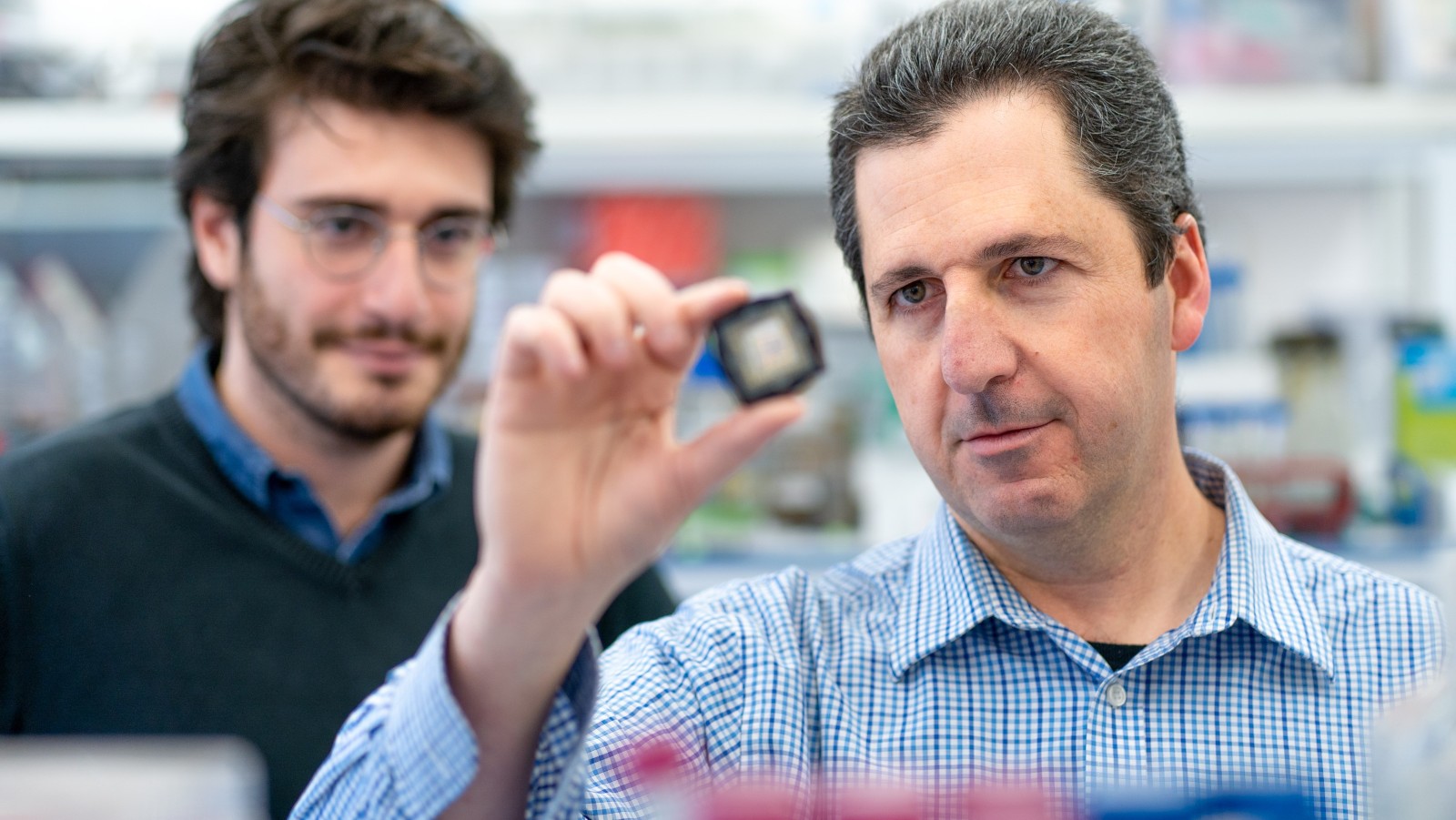

Jonas Salk, developer of the polio vaccine, holds a rack of test tubes in his lab in Pittsburgh in 1954. (AP)

Jonas Salk, developer of the polio vaccine, holds a rack of test tubes in his lab in Pittsburgh in 1954. (AP)

But Ford was undeterred. He directed the vaccination program to proceed, announcing plans to inoculate 1 million people per day by the fall — an unprecedented timeline the government struggled to meet.

300x240.png)