- Joined

- Jun 8, 2008

- Messages

- 56,758

I’ll start.

“

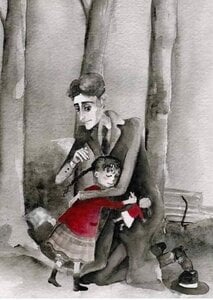

At 40, Franz Kafka (1883-1924), who never married and had no children, walked through the park in Berlin when he met a girl who was crying because she had lost her favourite doll. She and Kafka searched for the doll unsuccessfully.

Kafka told her to meet him there the next day and they would come back to look for her.

The next day, when they had not yet found the doll, Kafka gave the girl a letter "written" by the doll saying "please don't cry. I took a trip to see the world. I will write to you about my adventures."

Thus began a story which continued until the end of Kafka's life.

During their meetings, Kafka read the letters of the doll carefully written with adventures and conversations that the girl found adorable.

Finally, Kafka brought back the doll (he bought one) that had returned to Berlin.

"It doesn't look like my doll at all," said the girl.

Kafka handed her another letter in which the doll wrote: "my travels have changed me." the little girl hugged the new doll and brought her happy home.

A year later Kafka died.

Many years later, the now-adult girl found a letter inside the doll. In the tiny letter signed by Kafka it was written:

"Everything you love will probably be lost, but in the end, love will return in another way."

#kafka #thedoll

“

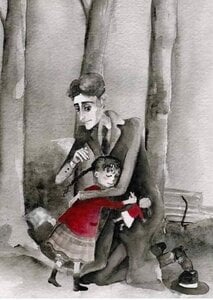

At 40, Franz Kafka (1883-1924), who never married and had no children, walked through the park in Berlin when he met a girl who was crying because she had lost her favourite doll. She and Kafka searched for the doll unsuccessfully.

Kafka told her to meet him there the next day and they would come back to look for her.

The next day, when they had not yet found the doll, Kafka gave the girl a letter "written" by the doll saying "please don't cry. I took a trip to see the world. I will write to you about my adventures."

Thus began a story which continued until the end of Kafka's life.

During their meetings, Kafka read the letters of the doll carefully written with adventures and conversations that the girl found adorable.

Finally, Kafka brought back the doll (he bought one) that had returned to Berlin.

"It doesn't look like my doll at all," said the girl.

Kafka handed her another letter in which the doll wrote: "my travels have changed me." the little girl hugged the new doll and brought her happy home.

A year later Kafka died.

Many years later, the now-adult girl found a letter inside the doll. In the tiny letter signed by Kafka it was written:

"Everything you love will probably be lost, but in the end, love will return in another way."

#kafka #thedoll

300x240.png)