- Joined

- Feb 29, 2012

- Messages

- 12,331

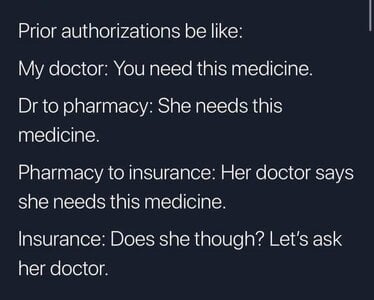

I find your objection to physicians investing money somewhat puzzling. A physician who is financially independent is one who is not beholden to private equity or a health system and can practice as he/she chooses. Yes, My husband and I have investments including real estate - that doesn't play into my practice of medicine at all (except for my retirement date). I suspect we are in the 1% but I really don't know (and anyone who was a casual observer of our life would never be able to tell). That doesn't make me any less of a physician or devalue my experience at all.

I don’t understand her posts either. DH made $27,000 a year in residency. They didn’t up the salary with outcry. They limited the work week to something like 75 hours and maybe threw in retirement (we didnt have an institutional retirement plan so we didn’t start saving until we were 30).

We have high net worth because of DH’s hard work and we live below our means. My house is less than 3,000 sqft, I drove a Honda minivan for 7 years and our kids went to private school and then public school and have part scholarships and all go to public university). We did inherit another house since both DH and his mother are only children.

I also don’t have a problem with doctors making money, especially those like my husband who are working 80-100 hours a week.

The reason DH’s company started as a multi speciality surgical clinic was because they could have an APMC, which offered more protections at the time than individual LLCs etc. and it was easier.

Last edited:

300x240.png)